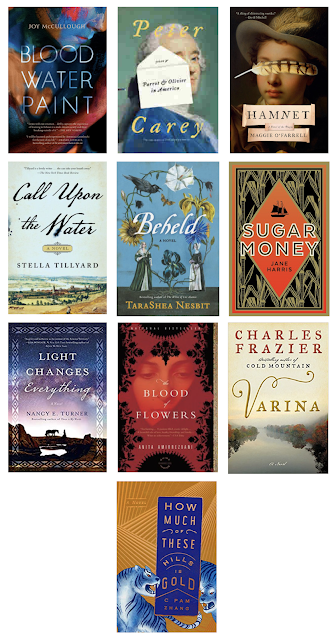

Despite the trauma of the pandemic (or maybe because of it), 2020 turned out to be an amazing year of reading for me. I managed to finish 44 books by the end of December, a personal record since I began keeping track in 2012 (you can see my yearly lists in the sidebar). I've been an avid reader my entire life, and I can hardly remember a year during which book after book not only entertained but impressed me. As a reader, it was exhilarating to read so many great novels; as a writer, it was both inspiring and somewhat daunting to encounter such craft. Blood Water Paint by Joy McCullogh, a powerful novel in verse about the seventeenth century artist Artemisia Gentileschi, was far and away my favorite of the year, but nine other books stood out as particular gems:

Sunday, January 3, 2021

Ten Favorite Reads of 2020

Wednesday, November 11, 2020

Why Read Historical Fiction Set in Sixteenth Century France? Reason #10

Over the past few weeks, we've examined ESCAPE, RELEVANCE, DRAMA, EMOTION, GLITZ, HISTORY, FRANCE, CHATEAUX and LITERARY LINEAGE as reasons to read historical fiction set in sixteenth century France. All of these contribute, in their own way, to our culminating reason...

Reason #10--DIFFERENCE

Trends arise in historical fiction, as they do with most cultural phenomena. A particular book will capture the attention of a significant number of readers, who, having enjoyed what they just read, want more. They start looking for other books that share a similar setting or topic or structure. Writers (who, of course, are readers, too) participate in the trend by creating what the public wants; agents and editors (whose job is to sell books) actively seek out manuscripts that meet those criteria. Within a couple of years (remember, it takes 18+ months from the sale of a manuscript to the appearance of the published book on the shelves), a trend has been established. A significant number of newly published works will feed the craze, even to the point of rehashing characters and plotlines. Eventually, however, readers do tire of the trend and authors run out of material to sustain it. At that point, a new book or topic garners attention and the cycle recommences. Trends are not necessarily sequential; they overlap, differ in length, and vary in detail and emphasis depending on audience and genre. One truth holds, however: it is quite difficult, if not impossible, to predict what the public will desire next, once they've had their fill.

Since I began writing historical fiction, I've witnessed several trends in the genre. Back in the early 2000's, Tudor fiction was all the rage. Inspired by Philippa Gregory's THE OTHER BOLEYN GIRL, published in 2001 and filmed in 2008, this trend focused on marital machinations at Henry VIII's court.

Anne Boleyn was by far the favorite protagonist, but the trend produced countless novels about all of Henry's wives. It expanded to include the Elizabethan court

as well as peripheral characters like Thomas Cromwell.

Eventually, however, writers exhausted the historical material and satiated their readers. Although Tudor-era fiction continues to draw a devoted subset of readers, its widespread appeal dampened and new trends came to the fore.

Overlapping the Tudor trend was that of "marquee characters." This was essentially the writing of fictionalized biographies of historical personages immediately recognizable to the reading public. This trend included novels about Marie Antoinette,

Thomas Jefferson,

and Nefertiti, to name only a few.

For many years, few editors would consider novels featuring fictional characters in a historical setting. They felt that readers wanted both the thrill of recognizing the portrait/name on the cover and the satisfaction of learning more about these famous men and women. Novels that relied on fictional characters as protagonists, no matter how accurate the depiction of historical events in the novel or the historical backdrop against which fictional events played out, were considered less appealing to readers. Biographical fiction can be challenging to write, as the sequence of events in a person's life does not always follow a particularly engaging dramatic arc. Many authors addressed this problem by narrating the famous subject's story from the perspective of a fictional servant or friend. Although biographical fiction will always enjoy a prominent place in the range of historical fiction, readers and publishers have in recent years given warmer reception to fictional protagonists inserted into well-research historical settings.

The most current trend in historical fiction is that of fiction set during World War II. This trend began in the mid-2000's with the publication novels like Marcus Zusak's THE BOOK THIEF.

Friday, October 23, 2020

Why Read Historical Fiction Set in Sixteenth Century France? Reason #9

Two reasons left! As a literature professor as well as a writer, I hold this one close to my heart.

Reason #9--LITERARY LINEAGE

Current historical fiction set in sixteenth century France participates in a rich tradition stretching back to the seventeenth century. In fact, the novel most scholars consider to be the very first historical novel written in French was set during the sixteenth century--La Princesse de Montpensier by Madame de La Fayette.

Penned in 1662, La Princesse de Montpensier is set a hundred years earlier, during the Wars of Religion. With great psychological depth, it tells the story of Renée d'Anjou-Mézières, a young noblewoman trapped in a loveless marriage, who falls victim to her passion for the Duc de Guise. Guise's friend, the Duc d'Anjou (who will take the throne as Henri III), himself becomes enamored of Renée, with disastrous results. La Fayette's novel is the first to take actual historical personnages as characters and set them in circumstances in which historical tensions and events (the 1572 St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre) are intrinsic to the plot. The novel was made into a successful film by noted director Bernard Tavernier in 2010

The twentieth century saw an explosion of interest in sixteenth century France as a setting for historical fiction. In 1935 and 1938, the German author Heinrich Mann wrote two novels about Henri of Navarre, who ruled as Henri IV.

Tuesday, October 20, 2020

Why Read Historical Fiction Set in Sixteenth Century France? Reason #8

The next reason I'll propose for reading historical fiction set in sixteenth century France is a corollary of Reason #7--FRANCE, but one that merits its own mention...

Reason #8--CHATEAUX

France's scenic countryside is dotted with thousands of castles. They range from ruined medieval fortresses

|

| Château Galliard |

to elaborate nineteenth century wine estates

|

| Photo credit |

|

| Photo credit: Zairon |

In 1515, François I and his wife Claude ascended to the throne. At Claude's urging, François began to refurbish the château de Blois, which had been used by French kings since the 13th century. He built a new wing with a spiral staircase at its center and consolidated his prodigious collection of books in the library. However, after Claude, mother of his seven children, died at the age of 24, François neglected Blois in favor of other palaces. He moved his library to Fontainebleau and seldom returned to Blois. Perhaps memories of his years there with Claude, of whom he had been fond, made François uncomfortable? Later in the century, Henri III resided at Blois with his mother, Catherine de Medici, during the chaos of the Wars of Religion. In December 1588, Henri summoned to Blois the Duc de Guise, a powerful and charismatic Catholic leader who nurtured ambitions for the throne. Once arrived, the Duc was assassinated by the king's body guard as the king looked on. How is that for an inciting incident, or a novel's climax?

|

| Photo credit: Tim Sackton |

|

| Chaumont. Photo credit: Tim Tim |

Friday, October 16, 2020

Why Read Historical Fiction Set in Sixteenth Century France? Reason #7

Today's reason almost goes without saying...

Reason #7--FRANCE

France is the most popular travel destination in the world, visited by 89 million foreign tourists in 2018 alone. The country's vineyards

beaches

mountains

tug at the hearts and pursestrings of enthusiastic travelers and compilers of bucket lists the world over. Paris tops New York on lists of "Most Visited Cities" and flaunts its undisputed title as the "Most Romantic." Its cultural attractions, like the Musée du Louvre, the Eiffel Tower, and Arc de Triomphe, as well as its luxury boutiques, fine restaurants, and outdoor cafés, are a perennial draw. For well-seasoned travelers and armchair dreamers alike, France holds a distinctive and dynamic appeal.

Monday, October 12, 2020

Why Read Historical Fiction Set in Sixteenth Century France? Reason #6

ESCAPE, RELEVANCE, DRAMA, EMOTION, GLITZ are the factors we've examined so far. Now it's time for one that, though obvious, nevertheless deserves attention...

Reason #6--HISTORY

In today's educational landscape, the study of history hardly occupies a prominent position. With so many other subjects clamoring for attention, history often gets shunted aside. Yet the study of history is essential to the healthy functioning of a modern republic. An old aphorism holds that "Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it." A thorough understanding of history prepares a country to move confidently into the future, equipped to identify challenges and hazards and able to address them without making costly, avoidable mistakes. Familiarity with the past also helps individuals define and select the ideals and aspirations they wish to live by and strive for.

|

| photo credit |

Reading historical fiction is an effective way to supplement the formal study of history. Some might object that it would be more valuable to read nonfiction about historical topics instead of novels, but fiction offers some distinct advantages in a non-academic setting. First of all, it is more readily accessible to a wider range of readers. Readers who seek entertainment are more likely to pick up a novel than a history tome that might uncomfortably remind them of schoolwork. As they engage with characters and follow the twists and turns of the plot, however, they absorb the factual information that infuses the story--a real-life example of a spoonful of sugar helping medicine go down! Their encounter with historical events and characters in the novel might pique their curiosity and send them to nonfiction sources to learn more. In any case, the reader has been introduced to historical material they might never have chanced upon otherwise. The historical novel serves as a gateway into deeper knowledge of and appreciation for history.

Secondly, reading historical fiction allows readers to discover the eras, events, and individuals that truly interest them. Historical fiction covers a wide range of countries and time periods. Readers can benefit from this plethora of options by sampling different combinations of settings, eras, and narrative techniques. Some readers like biographical fiction, which dramatizes the life of a prominent historical personnage; others prefer to read about fictional characters acting in a historical setting defined by historical events. Battle fiction interests one type of reader; novels told from the perspective of women or the marginalized speak to another. Nonfiction history books are often quite specific and compartmentalized, making it difficult for non-academic readers to locate general interest books about a certain era. Reading historical fiction provides a quicker entry into the historical scene. Readers can enjoy a novel whether or not they they come to it with previous knowledge of the time period, and will most likely leave it knowing more about the era or person than they did before.

Finally, and most importantly, historical fiction offers readers something that non-fiction cannot--access to the thoughts and emotions of historical characters. Whereas history teaches facts--names, dates, ideologies, and events, historical fiction allows readers to explore people's relationship to those facts. It gives a human face to history by imagining how people caught up in historical events might have reacted to them. How did a galley slave preserve his sanity during endless days of forced rowing? What might cause one neighbor to denounce another who embraced the reformed religion? How might a skilled female artist or poet in the Renaissance flourish, despite the disdain of male practicioners? Historians are discouraged from postulating the thoughts and emotions of the subjects they write about; the novelist, on the other hand, builds a story out of the very things the historian is forced to omit. In a novel, the historical context provides a challenge, a set of boundaries and conditions, which characters must confront and overcome in historically appropriate ways. The historical element that lovers of historical fiction prize is not an end in itself, but serves to highlight the resilience and breadth of the human spirit. In a historical novel, the history is not the story; how the characters both shape and are shaped by that history is.

Friday, October 2, 2020

Why Read Historical Fiction Set in Sixteenth Century France? Reason #4

ESCAPE, RELEVANCE, and DRAMA--these are the reasons I've examined so far to promote historical fiction set in what scholars call the "Early Modern" era. Today, we'll talk about...

Reason #4: EMOTION

Although manners and mores have changed over the centuries, basic human emotions have not, and emotion is what drives fiction. Love, rage, guilt, spite--such emotions define the human experience. Whether a character wears spandex yoga pants or an embroidered bodice, tees off on the fairway or parries a sword blow matters much less to readers than the emotions the character experiences.

Current scientific research indicates that reading literary fiction increases empathy in readers--by placing themselves in the minds of characters and viewing a fictional world from an unfamiliar perspective, readers become more adept at putting themselves in other people's shoes in real life. The most powerful way readers connect with characters is through shared emotion. Reading a character's emotional experience on the page stirs readers' own emotional memories. This thrill of recognition forms a bond between reader and character, one that encourages the reader to follow that character into an exploration of other emotions that might not be as familiar. As they identify with characters through shared emotional experience, readers come to reconsider their own past experience in more nuanced ways. They not only increase their ability to connect with other people, but they broaden the spectrum of their own remotional response.

By reading novels set in the distant past, readers can experience certain emotions in a more intense way than modern life usually affords. In the sixteenth century, the world was a dangerous and often brutal place, both physically and socially. Emotions like terror, humiliation, and shame, which are seldom experienced today, were common responses to unsettling and unexpected events. Hiding as enemy soldiers ransacked your town and ravished your neighbors' daughters must have inspired a fear quite unlike that of watching the value of your 401k slide. Saying goodbye to a navigator husband boarding a leaky galleon for a voyage to the New World was infintely more traumatic that dropping your spouse off at the airport for a business trip. Being ostracized as an adulterer or tortured for your religious beliefs hardly compares to wagging tongues and cancel culture. Reading historical fiction set in the sixteenth century provides us an opportunity to experience strong sentiments we might never feel in our real lives, thereby allowing us to expand our emotional literacy and our ability to empathize.

|

| Photo credit |

Even as historical fiction allows us to experience the intensity of these emotions, however, it protects us from their real-life consequences. We can cringe in horror as a heretic burns at the stake without entangling ourselves in debate over whether such punishment is justified. We can experience the joy of a child's sudden recovery from illness without having to evaluate and choose among treatments. We can indulge in the thrill of an illicit love without worrying about the destiny of our souls. Sheltered from the repercussions of the emotions depicted, we can indulge in them with abandon, strengthening our capacity to understand what others think and feel. Ultimately, by observing how actions trigger emotions and emotions inspire actions in the novel, we learn how to control our own emotions, the better to direct the course of our lives. The fiction serves as a heady and gratifying but ultimately cautionary tale--one that delights and entertains, even as it teaches.

The perilous and precarious world of sixteenth century historical fiction will take readers from the heights of ecstasy and glory to the depths of cruelty and despair, acquainting them with envy, lust, indignation, hatred, fear, joy, courage, and love along the way. It leaves but a single emotion untried, the one readers are most eager to avoid: boredom.

Wednesday, September 30, 2020

Guest Post by Karen Odden: The “Mysnomer” in the Label “Historical Mystery”

I asked Karen Odden, author of the Victorian mysteries A DANGEROUS DUET (2018) and A TRACE OF DECEIT (2019) about the differences between historical mystery and straight historical fiction. Here's what she had to say!